AMOY Research & Monitoring in North Carolina

Research

The American Oystercatcher is listed as a “species of special concern” in North Carolina. The objectives of our research are to evaluate the status and viability of North Carolina’s oystercatcher population, as well as factors that may be affecting the population. We would also like to understand the relationship of North Carolina’s population to other populations along the east coast of the United States.

Oystercatcher population dynamics in response to management

Due to low population abundance, overall population decline, and continued coastal threats, the North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission considers the American Oystercatcher a species of greatest conservation need (2015) and the U.S. Shorebird Conservation Plan Partnership (2015) considers it a species of conservation concern. Researchers at North Carolina State University are using a combination of methods to assess the status of American Oystercatchers within the state and determine how management practices might influence this. An initial step of this research modeled population growth. The model suggested that the state’s oystercatcher population is nearly stable and that current management efforts, which are focused on decreasing nest and chick loss, are likely to support population inclines. However, these results were limited in scope. Oystercatchers are relatively-long lived shorebirds, making sub-adult and adult survival rates disproportionately important in determining the health of the population, if these rates are low, or if adults are recruiting into the breeding population at a low rate, then the population will continue to decline, even if 100% of parents were to produce a chick each year. Our initial demographic model relied on estimates from Eurasian Oystercatchers for some of these more important rates for older oystercatchers, meaning that they may not be at all accurate for American Oystercatchers in North Carolina. Additionally, the model assumed an equal sex ratio. For a monogamous breeder such as the American Oystercatcher, ignoring sex-dependent survival and skewed sex ratios overestimates the number of male-female pairs available to recruit into the breeding population. This may lead to overestimates of species population projections and underestimates of extinction rates (Saether and Bakke 2000, Steifetten and Dale 2006, Eberhart-Phillips et al. 2017). Skewed sex ratios are common in avian species and are regularly found to be a root cause of biased estimates in population projections (Boukal and Berec 2002, Donald 2007). Such biases have been documented in other waterbird and shorebird species specifically (Szczys et al. 2001, Eberhart-Phillips et al. 2017).

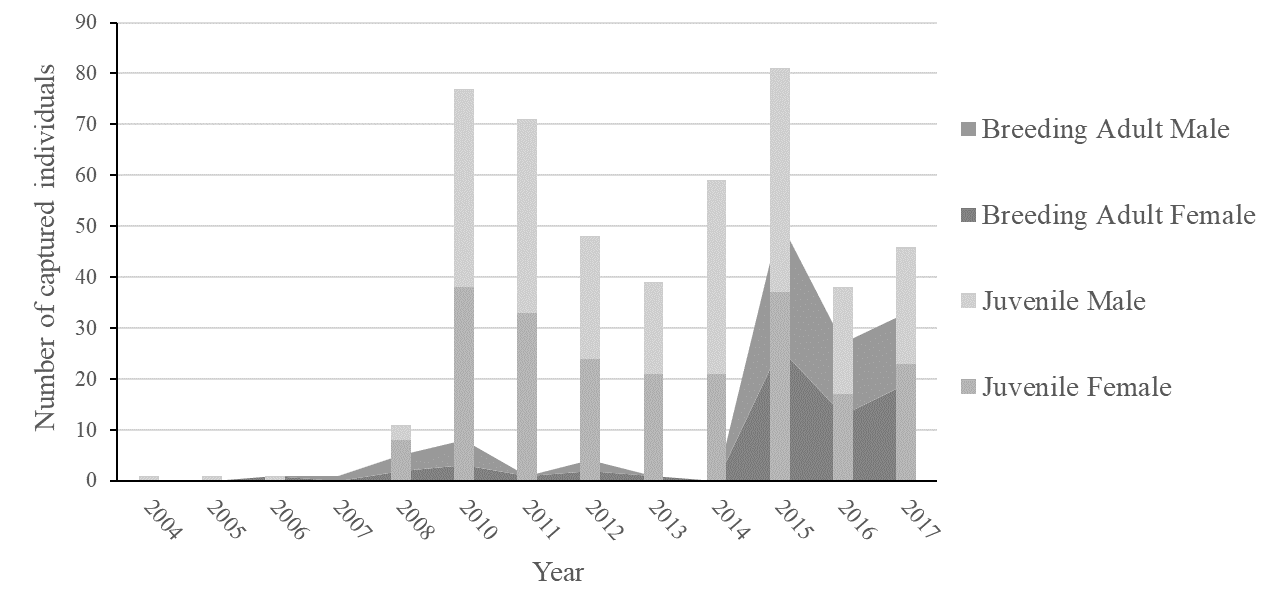

Current efforts are underway to use the American Oystercatcher banding database to estimate the missing parameters through a series of multi-event, multi-state capture-mark-recapture models. Researchers in North Carolina have been collecting feathers from oystercatchers during capture and banding protocols. With funding from NC SeaGrant researchers from North Carolina State University and Audubon NC have sent the feathers to be sexed by the Alvez lab at University of Porto. We are currently using this information to assess how differences in management at properties across North Carolina, might influence oystercatcher populations post-fledging and how males and females might be affected differently by these management decisions.

For more information, contact Shilo Felton.

Number of feather samples from male and female American Oystercatchers captured in North Carolina.

Field experiment testing the behavioral and physiological responses of beach-nesting adults to off-road vehicles

Beach driving remains a popular activity on many beaches worldwide. Within North Carolina, this has been of particular concern to managers who are expected to balance visitor use with the conservation of natural resources. While previous research from the Simons lab at North Carolina State University has suggested that recreational activities can reduce nest and chick survival rates, an experimental approach allows us to better understand the immediate effect that passing vehicles might have to nesting oystercatchers, even when vehicles are prevented from impacting chicks directly. Our experimental design assumed that vehicles were prevented from running over nests or stopping in the immediate vicinity of oystercatcher nests. Using security cameras near the nests and microphones installed within nests, we compared the nesting behaviors and heart rates for pairs during driving trials to behavior and heart rates immediately before the start of driving trials. Results suggest that oystercatchers spend less time on their nests during driving trials and tend to lower their heart rates when vehicles are present. Though their flight response tends to wane as nests get closer to hatching, the lowered heart rate does not. This suggests that oystercatchers are not necessarily habituating over time, but instead are more likely to stick close to their nests to protect their nests as they become more invested. Our results also suggest a high level of variability in responses between individuals, suggested that the level of response might be an indicator of differences in personality between birds. View paper (PDF).

For more information, contact Shilo Felton.

Annual Breeding Surveys

A study of breeding American Oystercatchers in North Carolina was initiated in 1995 on South Core Banks, Cape Lookout National Seashore to document nesting success. Subsequent research expanded the study area to include all nesting oystercatcher pairs on Cape Lookout and Cape Hatteras National Seashores and expanded the scope of the work to investigate survival, fidelity, movement, disturbance and depredation.

We are currently monitoring oystercatcher breeding success at several locations in North Carolina. Cape Hatteras and Cape Lookout National Seashores comprise over 160 km of barrier island habitats and are monitored by the National Park Service. Audubon North Carolina monitors estuary islands in Ocracoke Inlet, off the west end of Ocracoke Island, and in the Cape Fear River region. The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission manages dredge islands in Oregon Inlet, located between Hatteras and Bodie Islands. Habitat in these locations consists of a combination of natural and man-made islands: some provide public access and human habitation, while others are closed to public use.

Complete State-wide Breeding Surveys

The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission coordinates American Oystercatcher breeding surveys of the entire coast of North Carolina every three years, with previous surveys occurring in 2004, 2007, 2010, 2012, and 2014. For these surveys, all nesting pairs and single American Oystercatchers are counted.

In 2013, NCWRC worked with North Carolina State University (NCSU) and the Virginia Department of Game and Inland Fisheries to develop a sampling protocol that would build upon previous survey efforts, striving to survey more sites and to obtain estimates of the probability of detecting oystercatchers. For this more intensive sampling, the North Carolina coast was divided into plots, which were defined by habitat, management jurisdiction and ownership, and location size. Collaborators selected plots to survey for oystercatchers either once or multiple times (≥3) during the breeding season (mid-April through June), identifying nesting territories and single American Oystercatchers. These surveys were collaborative efforts that included the NCWRC, NCSU, Audubon North Carolina, Cape Lookout National Seashore, Rachel Carson National Estuarine Research Reserve, Cape Hatteras National Seashore, U.S. Marine Corps, Fort Fisher State Park, and Bald Head Island Conservancy. Data from this multi-agency study are currently being compiled.

Non-breeding Surveys

The North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission performs non-breeding surveys in Back and Bogue Sounds, Carteret County.

Since fall 2009, Audubon North Carolina has conducted regular non-breeding surveys in southeastern North Carolina to document use of habitat by non-breeding oystercatchers and resight bands. Survey sites are the Lower Cape Fear River, Masonboro Sound, Masonboro Inlet, Mason Inlet, Rich Inlet, and Topsail Inlet.

Past Projects

Previous research began with a study of South Core Banks in 1995, documenting low American Oystercatcher nest success and attributing loss to human disturbance. The low success sparked interest in the species and increased monitoring in the National Seashores and interior sites. Studies have since shown that mammalian predators are the major predator on both nests and chicks on the barrier island sites. There also appears to be an interaction between nest disturbance and depredation rates. A radio telemetry study on pre-fledging oystercatcher chicks illuminated causes of chick loss. A large-scale mark-recapture study was begun in 2008 to obtain reliable estimates of survival, recruitment, and other key demographic parameters and currently continues throughout much of the oystercatcher’s range.

Effects of human activity on American Oystercatchers breeding at Cape Lookout National Seashore

Cape Lookout National Seashore is a site of traditional American Oystercatcher breeding habitat. Although relatively undeveloped, the Seashore and surrounding area still host an array of human activities. We are conducting research through North Carolina State University to assess the effects of human noise and activity on American Oystercatchers nesting at Cape Lookout National Seashore in North Carolina. Our study is focused on the effects of various forms of anthropogenic activity, including military jet overflights, vehicles, and park visitors, on the behavior, physiology, reproductive success, and survival of American Oystercatchers at Cape Lookout. We employed a variety of technologies including; audio recorders to monitor sound levels, video cameras to monitor oystercatcher incubating behavior and beach activity, and microphones to monitor heart rates of incubating birds, to assess effects. Initial results show a minimal behavioral response to aircraft, and a potential behavioral response to vehicles.

For more information, contact Tracy Borneman.

Alternate nesting habitat use in North Carolina

Between increased human use and rising seas, America’s coastline is changing at unprecedented rates – barrier beaches are disappearing for those species who call it home. As an obligate coastal species exhibiting high visibility and site fidelity, the oystercatcher is an ideal species through which to consider those changes. Evidence suggests that the proportion of oystercatchers nesting on dredge spoil islands has increased but that success is reduced in these locations. The primary tradeoff for birds nesting on these islands is that there are no mammalian predators, but food acquisition requires leaving the nesting territory. Oystercatcher chicks are dependent upon their parents for food until after fledging. Therefore, one adult is forced to fly to a distant food source, leaving the second adult alone to defend the brood. This is energetically taxing on all members of the family group and may explain reduced nesting success of pairs on the dredge-spoil islands, as compared to barrier islands. We evaluate reproductive success by two metrics: the condition of chicks prior to fledging and the daily survival rate of nests. Chicks in 2011 were handled multiple times prior to fledging, in order to determine condition growth rates. This is being combined with a story of several years of productivity data to compare the overall success in the two types of site (barrier and dredge).

For more information, contact Jessica Stocking.

Partial removal of a raccoon population on a barrier island

Predator management to benefit breeding American Oystercatchers has been identified as a priority management strategy by the American Oystercatcher Working Group. Raccoon populations on the barrier islands of North Carolina are artificially high because raccoons benefit from the food, water, and shelter provided by humans. Closed systems such as isolated barrier islands provide an ideal opportunity to manipulate predator populations with minimal confounding factors. We are continuing research to evaluate the effects of a 50% reduction of the raccoon population on South Core Banks, Cape Lookout National Seashore in 2009-2010. We use a combination of telemetry and camera trapping to estimate the raccoon population before and after the removal and examine correlation between these estimates and productivity of prey species on the island. Results will be used to inform park management and other American Oystercatcher conservation programs about the costs and benefits of managing predator populations to benefit nesting oystercatchers.

For more information, contact Jessica Stocking.

Boat Disturbance

In 2010 and 2011 Audubon North Carolina collected data on the effect of boat disturbance on breeding oystercatchers on the Lower Cape Fear River and Ocracoke Inlet in order to quantify the impact of boat activity on oystercatchers using the intertidal zone and shoreline of islands.

Satellite Tracking

In the spring and summer of 2013, six adult oystercatchers were outfitted with 9.5-gram solar-powered satellite transmitters in order to study habitat use and migration strategies, as well as provide a portal for public interaction with and education about the species. A website, oystercatchertracking.org was created for internet users to follow the birds, two of which were successfully tracked on their migrations to Capers Island, South Carolina and Cedar Key, Florida. In subsequent years, we hope to deploy additional transmitters, including more advanced models that will provide GPS points for finer scale evaluation of habitat use during breeding, migration, and wintering.

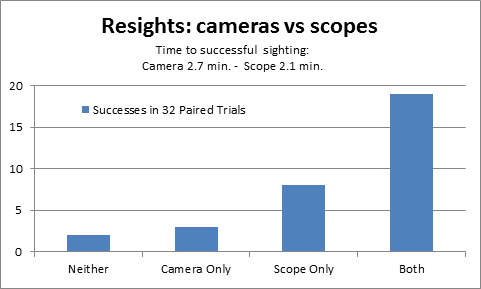

Camera Resight Experiment

To determine how cameras fared as a resight tool compared to spotting scopes, we had pairs of observers resight oystercatchers where one observer used an inexpensive Canon SX50 camera (~$300), and the other observer used a spotting scope. Below is a graph of the results.

We also tested the resighting range of the camera by photographing a banded oystercatcher decoy at four different distances: 25, 50, 75, and 100 meters. See the photos below (click to enlarge).

Banding

Color banding

We have been trapping and banding breeding American Oystercatchers on the Outer Banks of North Carolina since 1999. Our goal is to establish a color-banded population to study patterns of dispersal and survival of birds nesting along the Atlantic coast of the southeastern United States. We continually observe oystercatchers for re-sighting of these color bands. We are currently developing demographic models to investigate population trends.

Fecundity and annual adult survival are the only demographic parameters for which we have reasonably reliable estimates for our oystercatcher populations. Other important demographic parameters, including juvenile and sub-adult survival, are not known for American Oystercatchers. Long-term banding studies are important to generate better estimates of demographic rates.

North Carolina Banding Schemes

There may be occasional variation in timing and leg placement of banding schemes.

2013 – present: Duplicate green bands with white triangle-code configuration (three white engraved horizontally-oriented letters/numbers with one character above two characters) on upper legs; single metal band on either lower leg.

2011 – 2013: Green flag with white horizontal code (three white engraved horizontally-oriented letters/numbers) on one upper leg; green round band with white vertical code (three white engraved vertically-oriented letters/numbers) on other upper leg; single metal band on either lower leg.

2004 – 2013: Duplicate green bands with white horizontal code (two white engraved horizontally-oriented letters/numbers) on upper legs; single metal band on either lower leg.

2003: Colors used: Red, Yellow, Dark Blue, Green, Orange, White

- Upper Left: No band or one color band

- Lower Left: Green Flag over USFWS metal band

- Upper Right: No band or one color band

- Lower Right: No band or one color band or two color bands

View Historical Banding Information (PDF).

North Carolina Contacts

- Ted Simons – Department of Applied Ecology, NC State University

- Jon Altman – Cape Lookout National Seashore

- Sara Schweitzer – North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

- David Allen – North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commission

- Lindsay Addison – Audubon North Carolina

North Carolina Participants

- Audubon North Carolina

- Cape Hatteras National Seashore

- Cape Lookout National Seashore

- North Carolina Cooperative Fish and Wildlife Research Unit

- North Carolina State University

- North Carolina Wildlife Resources Commision